The Right Mind at the Right Time: An Example

Wednesday, October 03, 2018

|

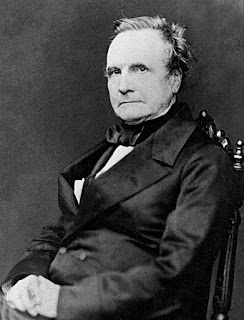

| Image of Charles Babbage via Wikipedia. |

I have nevertheless managed to squeeze in sporadic reading of Steven Johnson's fascinating book, Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World, which discusses the importance of the delight in novelty in motivating the people (at all levels) who drive historical change. Johnson has interesting and thought-provoking things to say, although I am pretty sure I don't agree with everything he seems to be saying so far. (I am only about a fifth of the way through.) But one passage reminded me a little of the following quote from Ayn Rand:

Speak on any scale open to you, large or small -- to your friends, your associates, your professional organizations, or any legitimate public forum. You can never tell when your words will reach the right mind at the right time. You will see no immediate results -- but it is of such activities that public opinion is made. [bold added] ("What Can One Do?", in Philosophy: Who Needs It, p. 202)Rand is obviously not discussing the technological or commercial innovation Johnson has focused on so far, but thinking is common to both -- and that is both an individual effort and can sweep the world with change when others see the value of original thinking. So there will be common principles behind innovation (and its adoption) in different fields, and it can be instructive to compare and contrast. With that in mind, consider how a mere amusement sparked a great mind to make connections that have since improved countless lives:

Conventional historical accounts are typically oriented around Great Events: battles fought, treaties signed, speeches delivered, elections won, leaders assassinated. Or the textbooks follow the long arc of incremental change: the rise of democracy or industrialization or civil rights. But sometimes history is shaped by chance encounters, far from the corridors of power, moments when an idea takes root in someone's head and lingers there for years until it makes its way onto the main stage of global change. One of those encounters happens in 1801, when a mother brings her precocious eight-year-old son to visit Merlin's museum. His name is Charles Babbage. The old showman senses something promising in the boy and offers to take him up to the attic to spark his curiosity even further. The boy is charmed by the walking lady. "The motions of her limbs were singularly graceful," he would recall many years later. But it is the dancer that seduces him. "This lady attitudinized in a most fascinating manner," he writes. "Her eyes were full of imagination and irresistible."(Wonderland, p. 8)The father of the modern computer would, one day, make his way to an estate sale to purchase the dancer which inspired him, and restore it for display in his home near his Difference Engine.

Steven Johnson is, as far as I know, no proponent of Rand, but his book touches on the importance of values in motivating both the thinking that makes great things possible and the adoption of that thinking or its products.

Regardless of Johnson's explicit views on those matters, his writing clearly embodies this broad lesson. I eagerly look forward to reading the rest of the book (when I can!) and improving my own thinking as a happy result.

-- CAV

No comments:

Post a Comment