Four Interesting Reads

Friday, September 27, 2024

A Friday Hodgepodge

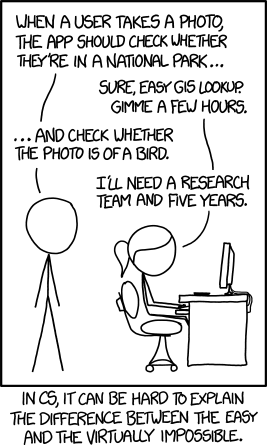

1. An XKCD Comic Turns Ten:

More at Simon Willison's Weblog.... It's amazing that "check whether the photo is of a bird" has gone from PhD-level to trivially easy to solve (with a vision LLM, or CLIP, or ResNet+ImageNet among others).

Image by Randall Munroe, via XKCD, license.

The key idea still very much stands though. Understanding the difference between easy and hard challenges in software development continues to require an enormous depth of experience.

I'd argue that LLMs have made this even worse.

Understanding what kind of tasks LLMs can and cannot reliably solve remains incredibly difficult and unintuitive. They're computer systems that are terrible at maths and that can't reliably lookup facts! [links omitted]

2. Paul Child repurposed his military logistics expertise to design Julia's kitchens:

It was Paul, however, who brought the design expertise to their partnership. During the war, he was part of the [Office of Strategic Services's] famed Visual Presentation branch, along with leading designers like Henry Dreyfuss and Eero Saarinen. Paul Child's particular speciality was designing war rooms, complete with situation maps, operational charts, models, and diagrams, including one for Lord Mountbatten at the South East Asian Command. In his postwar roles in the United States Information Service, Paul deployed these skills in the service of soft power and Cold War propaganda, curating exhibits showcasing American life abroad. He was also an accomplished photographer and artist. Julia gave him full share in her success, calling him "the man who was always there: porter, dishwasher, official photographer, mushroom dicer and onion chopper, editor, fish illustrator, manager, taster, idea man, resident poet, and husband." [footnotes omitted]You'll need to budget about 20 minutes for the whole read at Places Journal.

3. Fans of history and umami have a book to consider:

Although both the Phoenicians and the Greeks discovered the anchovy's pleasures, it is the Romans who first put it on the food map through their fish sauces, of which garum is the best known. The sauces were probably all produced using the same method: layers of fish were alternated with layers of salt in jars or vats and left to cure, often in direct sunlight, for anything up to a year. Its potency proved ambivalent: Horace called it a 'table delicacy'; he also said 'It stinks'. No argument there: when archaeologists started excavating a garum shop in Pompeii in 1960 they uncovered amphorae that still retained its distinctive aroma after nearly 2,000 years.The full review of A Twist in the Tail: How the Humble Anchovy Flavoured Western Cuisine appears at Englesberg Ideas.

4. A very rare neurological disorder is helping scientists understand facial recognition:

[Neuroscientist Brad] Duchaine first heard about PMO [prosopometamorphopsia aka demon face syndrome] while studying face blindness. He was surprised when studies and surveys suggested that around two per cent of the population develops the condition. In 2021, he created a Web site that asked people who see facial distortions to get in touch, in the hope that a similar hidden population might surface. Around a hundred and fifty people have reported facial distortions to his team -- a number suggesting that, around the world, thousands of people may experience them.This New Yorker piece might well remind fellow Oliver Sacks fans of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat with its skillful interweaving of the scientific and human sides of the story.

Given that many PMO patients don't have trouble seeing other body parts, or objects, the condition reinforces the idea that there are face-specific networks in the brain. But people with PMO can recognize faces, and this suggests that facial perception and recognition might be separate processes. (Some people with PMO see more intense distortions on strangers, whereas others see them more on loved ones; one patient said in 2012 that she saw the most extreme changes in her grandchildren.) Duchaine's findings have led him to a novel theory of how we see faces. Roughly a quarter of his patients, including Werbeloff, have hemi-PMO -- distortions that affect only half of the face. "The two halves of the face seem to be represented separately from one another, which is a surprise," Duchaine said. We may consider our lips to be one thing, but our brains seem to see them as the left side of the lip and the right side.

-- CAV

No comments:

Post a Comment